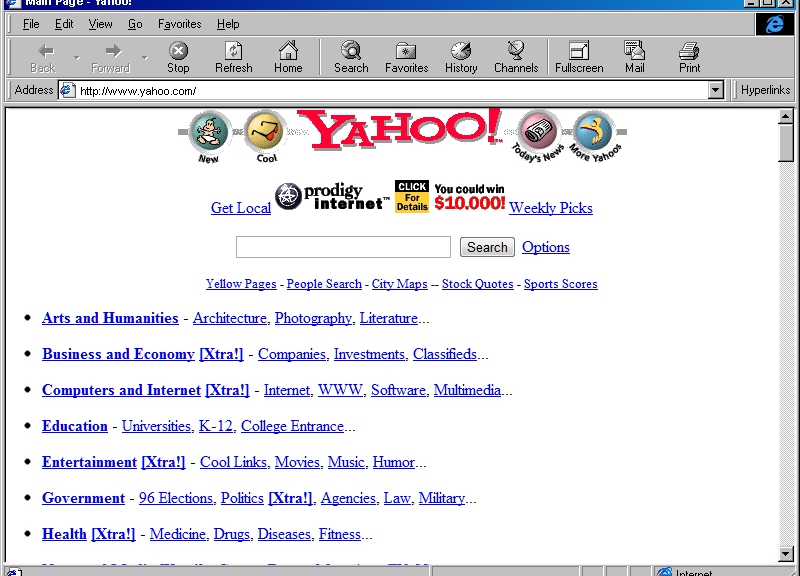

I’m old enough to remember when the internet looked like this. It was 1994, I was a first year college student, and the buzz in the dorms was about the amazing democratizing potential of this crazy new gizmo that politicians were still describing as “the information superhighway.”

The Web, we realized, would radically disintermediate information flows. Rather than a handful of information gatekeepers hoarding prestigious jobs in a few institution, everyone would be at the same time reader, writer and editor: leading to a radical decentralization and an explosion in information, engagement and understanding. As a 19-year old, I was genuinely excited about this looming, radical democratization of information; we all were.

Fast forward 20 years, and survey the state of reporting on, for instance, Africa:

Congo is the scene of one of the greatest man-made disasters of our lifetimes. Two successive wars have killed more than five million people since 1996.

Yet this great event in human history has produced no sustained reporting. No journalist is stationed consistently on the front lines of the war telling us its stories. As a student in America, where I was considering a Ph.D. in mathematics and a job in finance, I would read 200-word stories buried in the back pages of newspapers. With so few words, speaking of events so large, there was a powerful sense of dissonance. I traveled to Congo, at age 22, on a one-way ticket, without a job or any promise of publication, with only a little money in my pocket and a conviction that what I would witness should be news.

When I arrived, there were only three other foreign reporters in Congo.

Our technoutopia’s gone a bit pear-shaped, hasn’t it?

The wars in Congo – and the enormous journalistic crack they fell through – lay bare the strange, skewed ways attention flows in the internet age. The web has turned out to be a weapon of mass distraction, subtly undermining our ability to engage with the worst outrages of our time.

The problem isn’t that the web hasn’t fulfilled its democratic promise. It’s that it has, and only too well. Give people a choice between endless servings of ice cream and endless servings of broccoli and it turns out they’ll go for the ice cream, every time. The internet’s eroded the institutional pressures that we used to come under in place to pass on the informational sweets once in a while, opting for the kinds of journalistic vegetables that will nourish you but won’t give you a sugar rush.

I think it was Clay Shirky who explained the mechanism most clearly: the great 20th Century Newspaper was basically an elaborate mechanism to get the guy down the street who needed to sell a used washing machine to pay the salary for the Cairo Bureau Chief. The internet destroyed that model of subsidization: the guy down the street who needs to sell a used washing machine has no reason to kick any money down to Cairo anymore.

That’s a pretty old insight by now. Even the shock of grasping that nothing magical is going to come along to replace it is old hat. What we’re left with, in 2014, is the fall-out: that dystopian realization that what’s replaced the well-coiffed gate-keepers isn’t some radical hippie communicational democracy but photos of everybody’s cat.

These are the new rules of the game. You can love them or hate them but you probably can’t change them, so best to do what you can to work with them.

As an advocate facing radical indifference to an outrage whose “non-newsness” I can neither understand nor accept, it’s all rather upsetting. People will not share stories about starving refugees, and because they won’t editors won’t commission those stories, and because they won’t politicians won’t fund an even minimally adequate response.

I don’t know how, exactly, you go about explaining to a refugee mom in Eastern Chad that her child has to be stunted and anemic because there’s a little blue button on a screen with a thumbs-up logo that people in the West can’t bring themselves to affix to her suffering. But that seems to me about the size of it.